Macroecology

1 Macroecology

2 Evolutionary ecology of bird colours

2.1 Climate and colour evolution

Ecogeographical rules link bird phenotypes to spatial variation in climate and other environmental variables. Prominent ecogeographical rules describe the effects of climatic variation on size (Bergmann’s rule), appendage size (Allen’s rule), or coloration. Ecogeographical rules that refer to animal coloration include Gloger’s rule - which predicts darker animals in wetter regions - and the thermal melanism hypothesis (Bogert’s rule) - which predicts darker animals in colder regions.

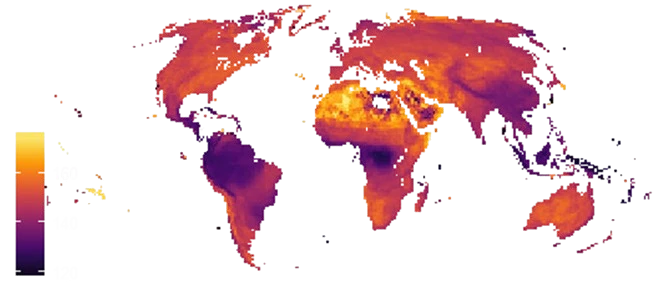

Our work revealed that both ecogeographical rules seem to apply to bird colours at a global scale (Delhey et al. 2019): birds are darker in regions that are wetter, and in colder regions. The most likely selection force behind the correlation between colour and temperature is thermoregulation: darker birds absorb more solar radiation, which is advantageous in cold environments, whereas lighter colours may be selected in warmer regions to avoid overheating. The selection mechanisms behind the effects of rainfall are less clear. Darker birds may be better camouflaged in darker, forested environments which are common in wet regions. Alternatively, selection may favour darker plumage because it makes feathers more resistant to abrasion and bacterial degradation, and these processes are more prevalent in humid and densely vegetated habitats.

We also found that the effects of rainfall on bird colours are much stronger than the effects of temperature. Depending on the geographic patterns of covariation between temperature and precipitation, climatic effects can work in concert and reinforce each other or work against each other. In the latter case, precipitation effects generally prevail over temperature effects, which explains why birds of the wet tropics are generally darker coloured. Correct interpretation of the ecogeographical rules of colour and how climatic effects interact is needed to predict potential effects of climate change. This led us to develop a framework to generate predictions associated with changes in temperature and precipitation (Delhey et al. 2020).

Currently, we are shifting our focus from variation in colour between species to variation within species, which should take us closer to the level at which selection is acting. We are using citizen science data on colour variation of European species (Common buzzard, Buteo buteo) and colour measurements of museum specimens of Australian birds to quantify the association between climatic factors and colour variation.

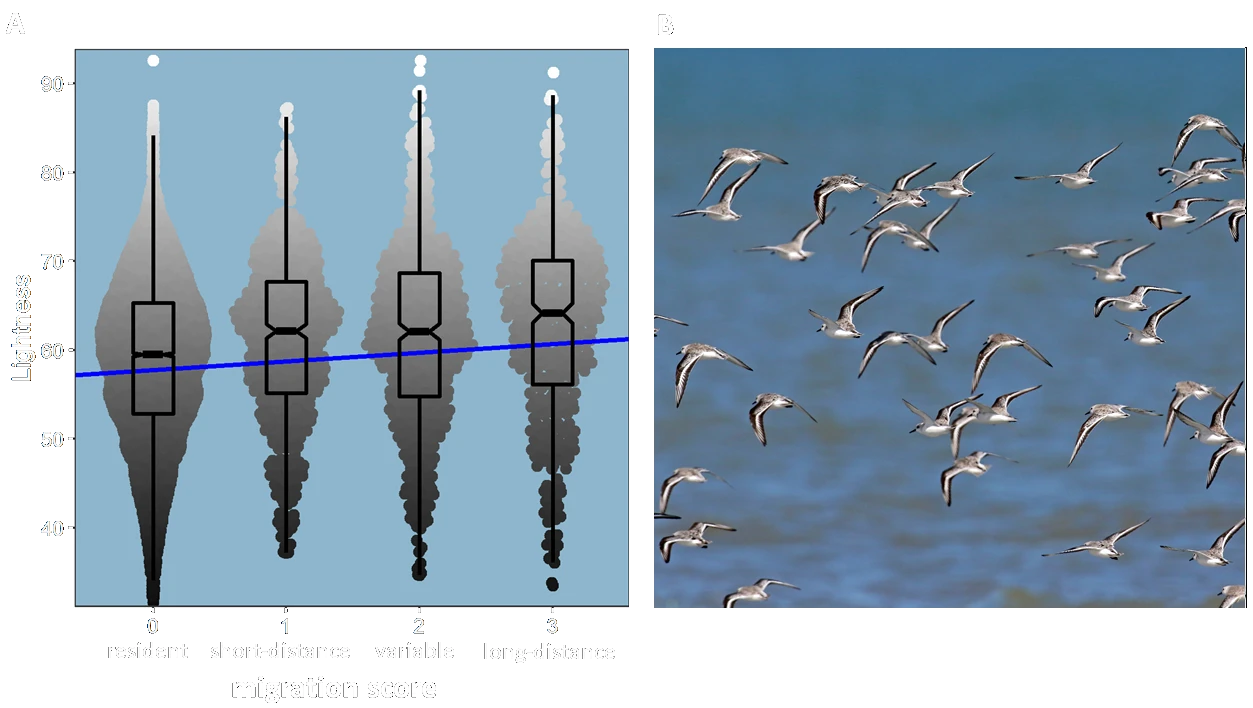

2.2 Migratory birds have lighter colours

One interesting spin-off of our work on climate and bird colour was inspired by recent research showing that long-distance migratory birds ascend rapidly after dawn and fly at higher altitudes during day than during night (doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.047, doi.org/10.1126/science.abe7291). One explanation of this behaviour is that birds migrate at higher altitudes, where the air is colder, to reduce the risk of overheating during the day. We hypothesised that if overheating due to solar radiation was an important selection force affecting migratory birds, the thermal melanism hypothesis would predict lighter coloured plumage in migratory species. This was indeed the case: across all species we found that long distance migratory birds had on average lighter plumage colours than short-distance migrants which in turn were lighter coloured than resident species (Delhey et al. 2021).

Our research inspired a poem (see thepoetryofscience). A first for us!

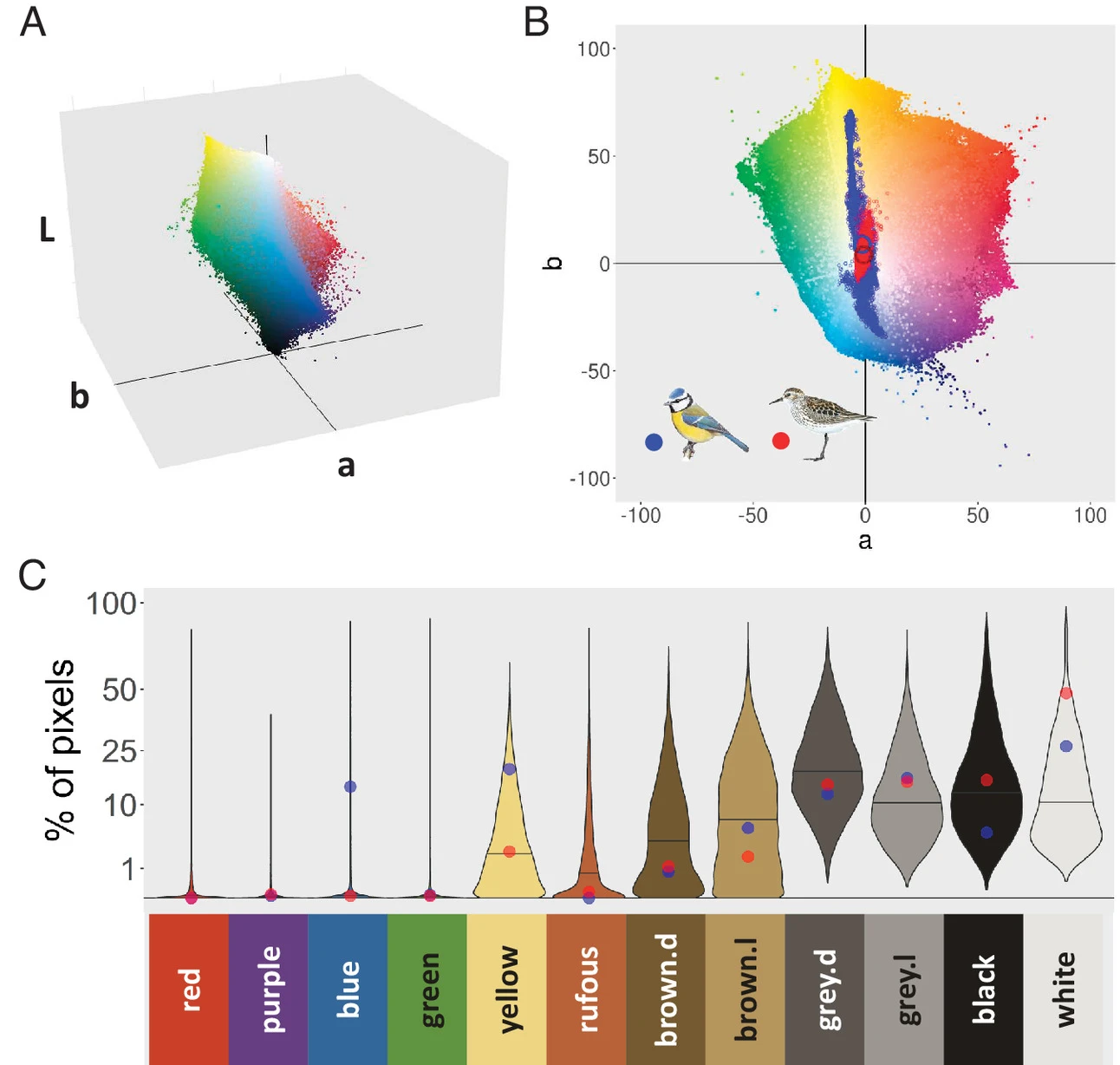

2.3 The colours of all birds

Birds come in a large variety of colours. While we have made substantial advances in understanding why some species are more colourful than others and in why males and females differ in colouration, it still remains unclear what makes different species have different colours. We were interested in answering basic questions such as why are ravens black, swans white and parrots green. A substantial set of theories and hypotheses exists to explain such variation, but these have not yet been put to the test at a large scale (all birds). In an attempt to address this issue (Delhey et al. 2023), we used book plates to quantify the proportion of the body covered by each of 12 colour categories for most species of birds.

We found that the most common bird colours were black and white and shades of grey and brown. More saturated colours such as yellow, green, red, blue and purple were much rarer. Females were more likely to be coloured brown, light grey or yellow, while males had more black, blue, red, purple and green. In general colours that are more common in males are ornamental colours used to attract mates or repel rivals, while common female colours tend to be more cryptic. Such colours tended to be favoured by strong sexual selection on males (polygynous species).

We find strong support for the idea that vegetation structure affects colour evolution because variation in background colours and light conditions determine which colours are good signals or serve to camouflage. Colours that are optimally cryptic in dense vegetation (e.g. forests) are not the same as colours good for camouflage in a desert. On average, forests were more likely to harbour cryptic colours such as green, yellow or brown, and potentially signalling ones such as red or blue. White plumage was more common in species that live in open habitats.

Birds more vulnerable to predators (smaller species and species that nest near or on the ground) tend to be coloured with more cryptic colours such as browns, light grey, green or yellow, while less vulnerable species (larger species that nest in safe locations) were more often coloured black, red and blue. We also found general support for the effects of climate and migration (see above).

While we found support for many of the existing theories and predictions, large amounts of colour variation remain unexplained. Differences in colour between species may have evolved to avoid hybridization, something that was not captured in our analyses. We are currently working on evaluating this possibility.

3 The macroecology of life-history traits

3.1 Extra-pair paternity

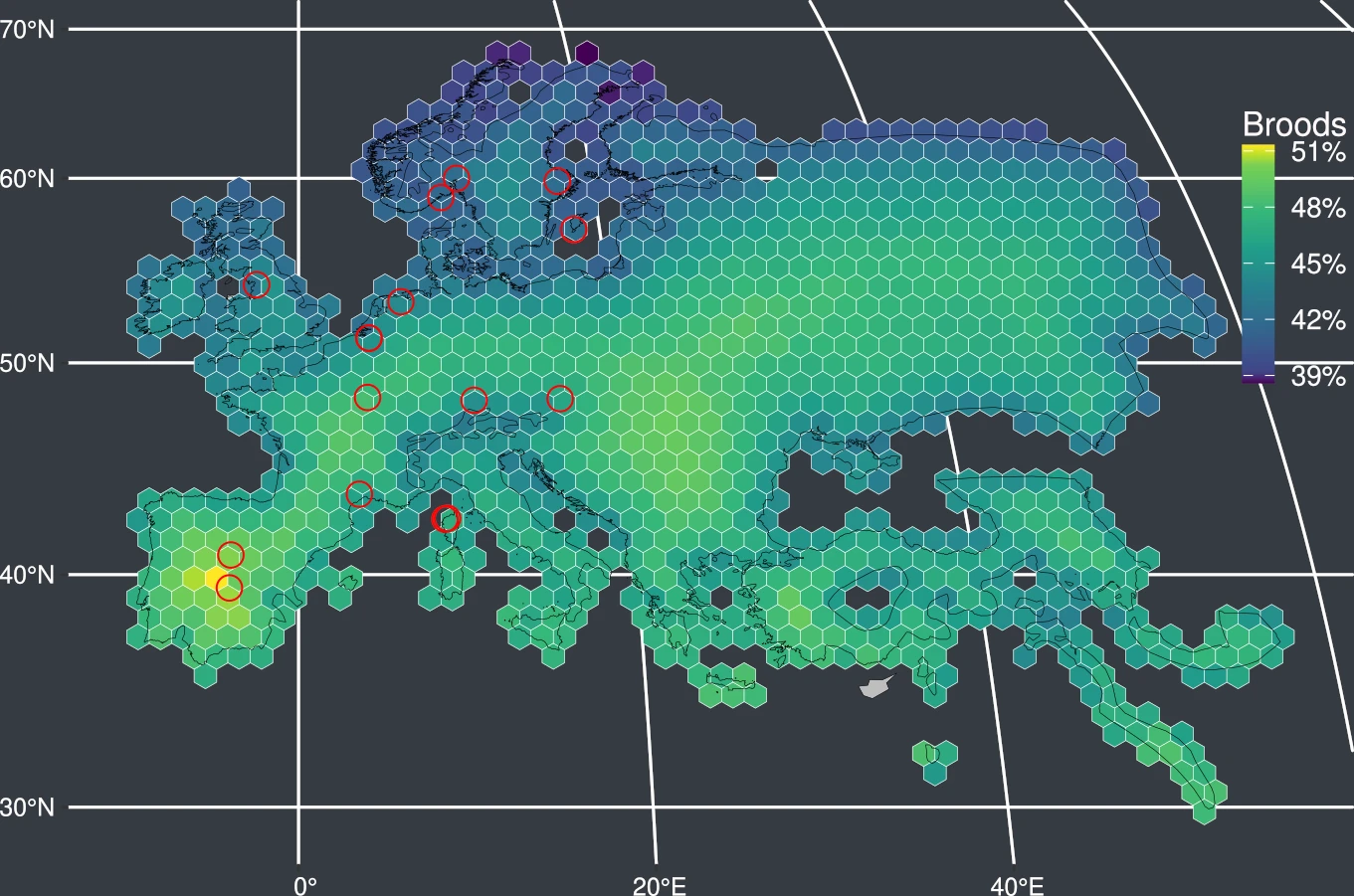

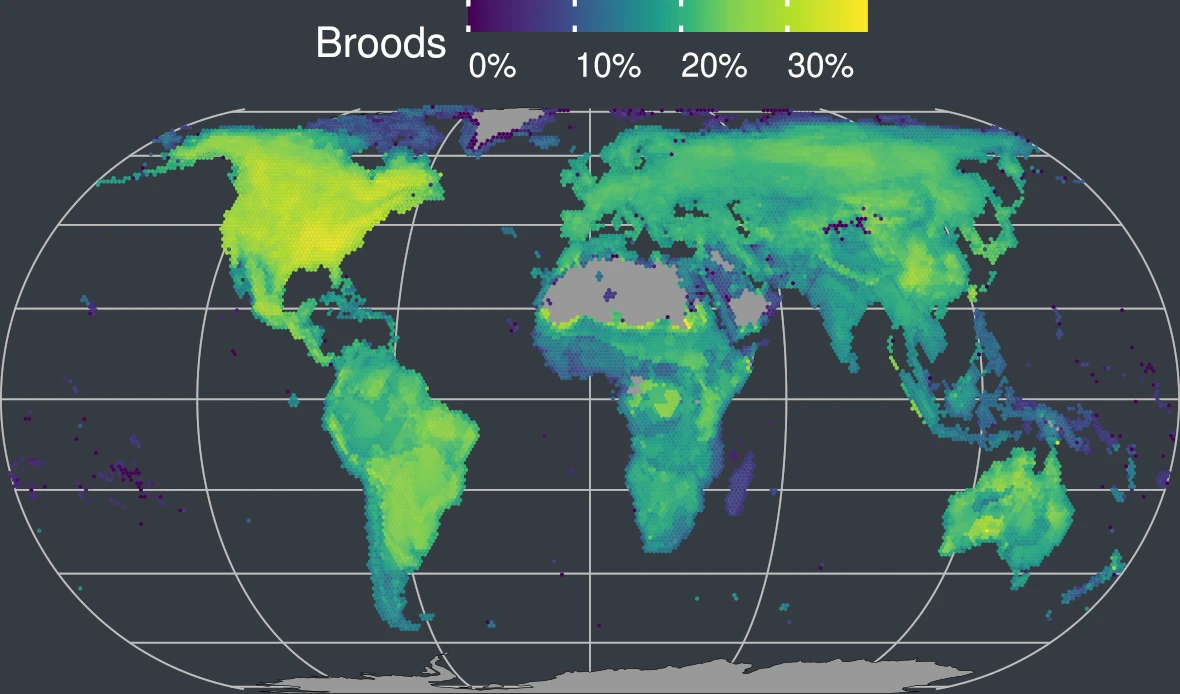

Extra-pair paternity is a key aspect of the mating behaviour of birds. The frequency of extra-pair paternity varies not only among individuals (see The zebra finch and The Blue Tit study systems), but also among populations and species. We explored the geographical variation in the frequency of extra-pair paternity among populations, species and species assemblages.

At population level, the frequency of extra-pair paternity decreases with latitude and increases with the distance from the breeding range boundary within the species’ breeding range.

At species level, the frequency of extra-pair paternity is negatively associated with generation length and pair-bond duration among species. At assemblage level (all the species existing in a particular area), the frequency of extra-pair paternity has a strong geographical signature: the highest values are found in the Palearctic and Nearctic realms and the frequency of extra-pair paternity decreases with latitude within the zoogeographical realms.

Our study suggests that the frequency of extra-pair paternity is the product of influences of multiple environmental, ecological and life-history factors and therefore follows a complex pattern of geographical variation. The results support the hierarchical explanation for variation in extra-pair paternity (C.-M. Valcu, Valcu, and Kempenaers 2021).

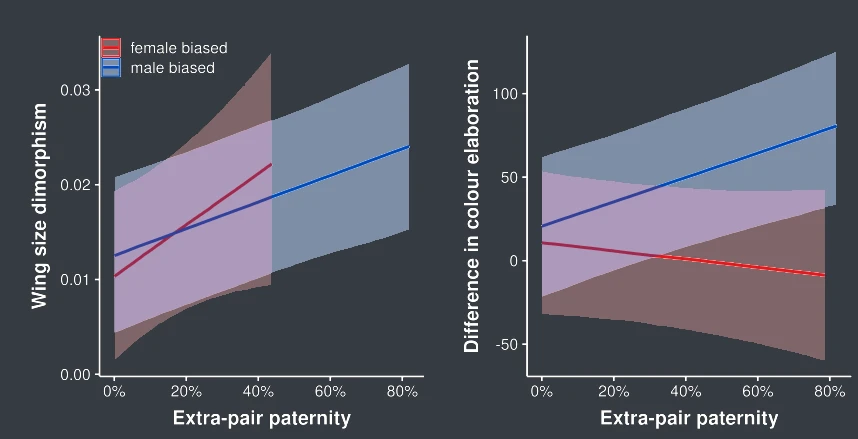

Extra-pair paternity can increase the variance in male reproductive success, and may thus intensify sexual selection and drive sexual dimorphism. In a further study, we investigated the connection between extra-pair paternity and sexual dimorphism in wing length and plumage colouration. Size and colour dimorphism are predicted by different reproductive, social and life-history traits, but extra-pair paternity plays a role in the evolution of both forms of dimorphism. High extra-pair paternity levels are associated with sexual dichromatism, positively in species in which males are more colourful and negatively in those in which females are more colourful. However, high extra-pair paternity rates are associated with increased wing length dimorphism in species with both male- and female-biased dimorphism (M. Valcu, Valcu, and Kempenaers 2023).

Currently, we are investigating the link between extra-pair paternity and sexual dichromatism arising from different mechanisms of colour production and in different body parts.

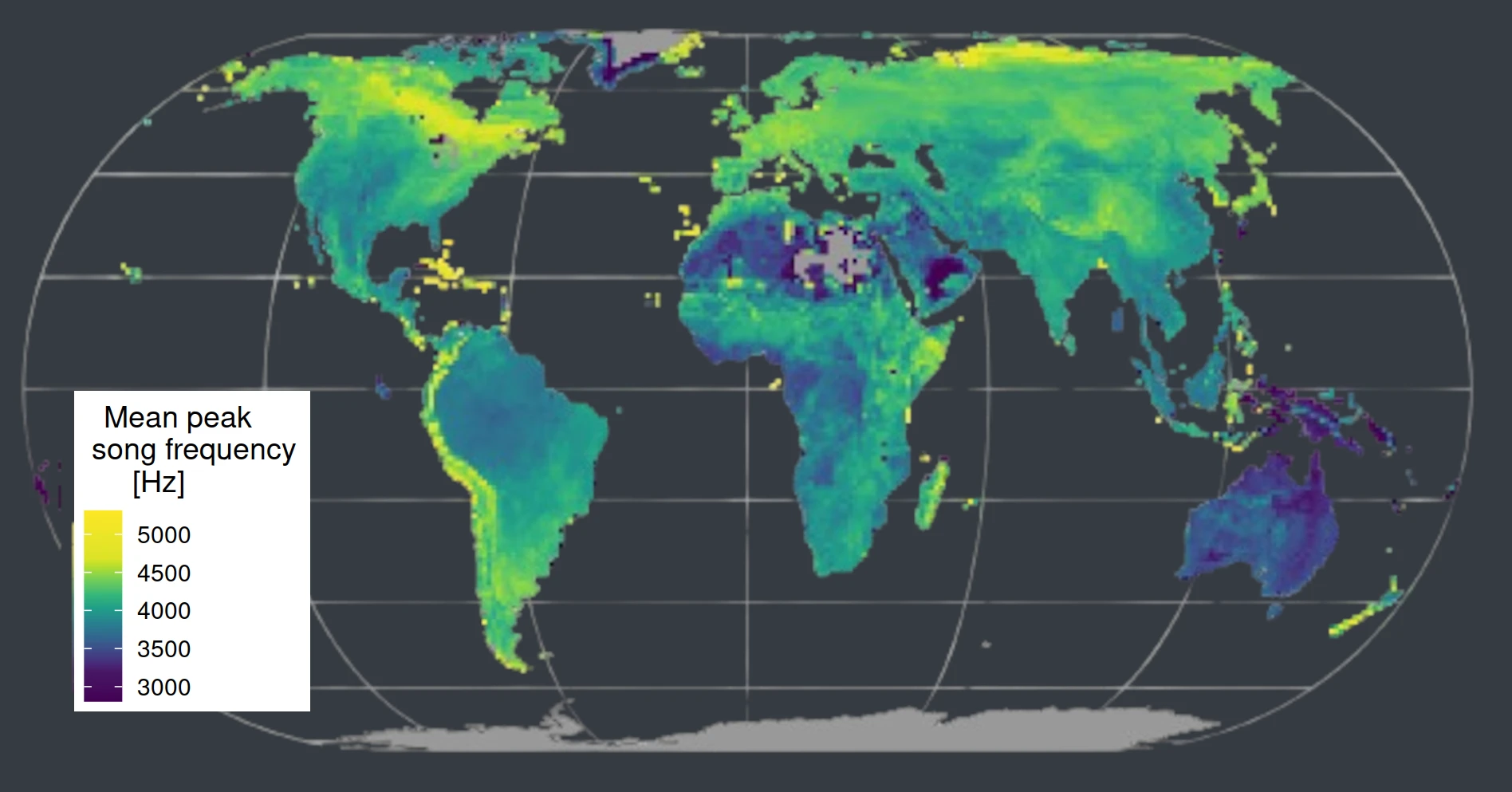

3.2 Song frequency

Most birds use acoustic signals to communicate. The properties of these signals are both under strong natural selection, because the environment influences sound propagation, and sexual selection, because signal frequency correlates with body size and sounds with different frequencies are perceived differently. To test these hypotheses, we analysed variation in peak song frequency in passerine species.

Song frequency decreases with increasing body mass and with male-biased sexual size dimorphism. However, we found no association between habitat and sound frequency. Fig 2a. Associations between peak song frequency and body mass, sexual size dimorphism and tree cover across passerines. Our study suggests that the global variation in passerine song frequency is mostly driven by natural and sexual selection causing evolutionary shifts in body size rather than by habitat-related selection on sound propagation (Mikula et al. 2021).

3.3 Timing of activity

Species vary widely in their timing of activity. Species which are active outside of the time period typical for the taxonomic order to which they belong are referred to as ‘time-shifters’. The evolution of nocturnality and the existence of time-shifters has been linked to two forms of competition: (i) direct interference competition (defending resources, imposing harm on competitors) and (ii) indirect exploitation competition (competition for resources). We investigated the relative importance of these two forms of competition on the occurrence of time-shifting among avian predator species.

Despite phylogenetic constraints, avian predators partition their time of activity to minimize the costs of direct interactions with competitors. Body size, as a proxy for competitive ability, appears to influence this partitioning strategy. Our study highlights the importance of interference competition as an evolutionary driver of time-shifting and suggest a role of body size in mediating the mechanism of time partitioning (Pei, Valcu, and Kempenaers 2018).

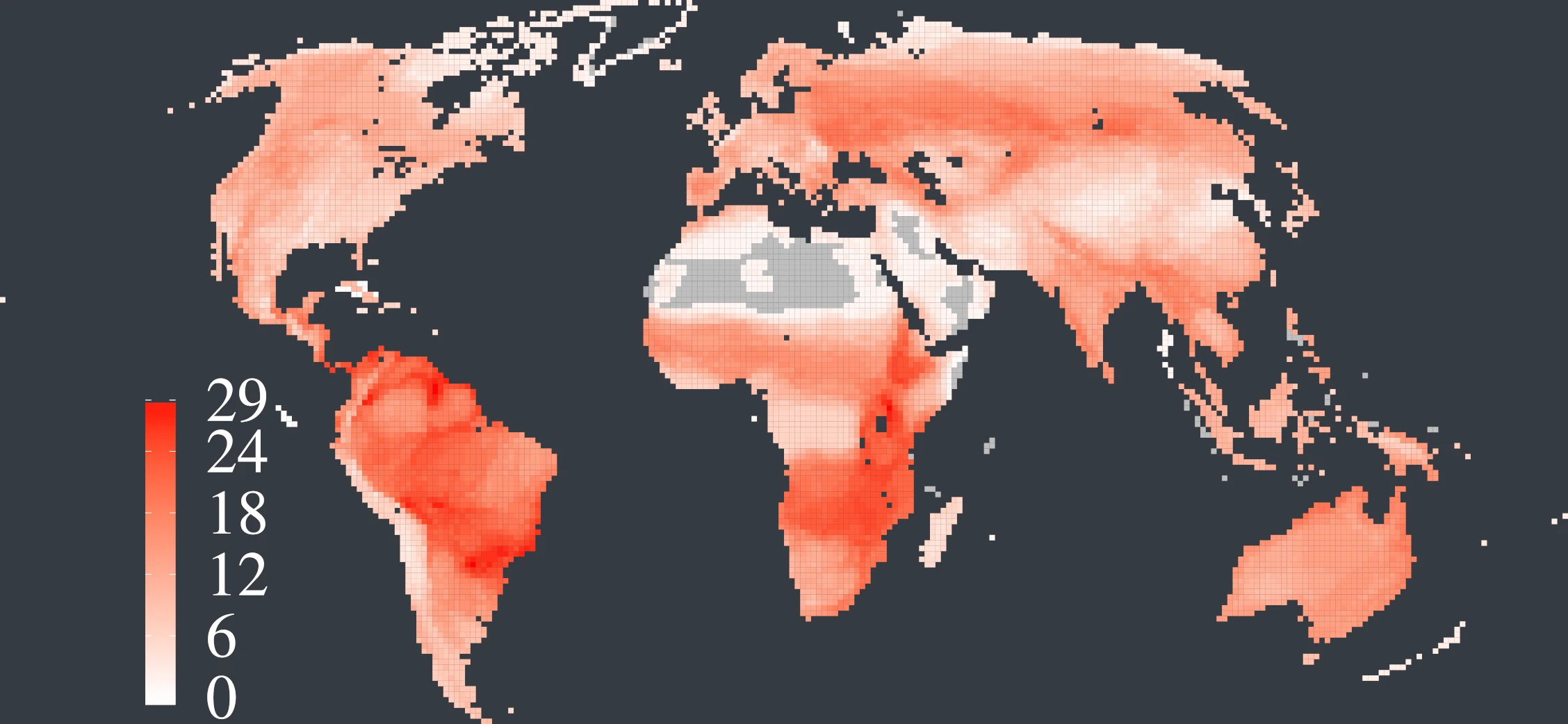

3.4 Parental investment

Maternal investment (e.g. clutch size, egg size) varies among species with different mating systems, as well as within the breeding range of each species, depending on the environmental conditions of the breeding location. Meanwhile, previous research from our group indicates that breeding site fidelity and the opportunity for local adaptation vary among species with different mating systems (Kempenaers and Valcu 2017; Kwon et al. 2022). Based on these findings, we predict different degrees of inter-population differentiation of maternal investment in monogamous and polygamous species, respectively. We are currently investigating the relationship between maternal investment, and the mating environment and mating system in shorebirds, known for their wide range of mating and parental care systems (Bulla et al. 2016).

4 Resources

We developed rangeMapper (M. Valcu, Dale, and Kempenaers 2012), an open source front end R package for macroecological studies designed to serve as an interface between the spatial and the statistical tools offered through the R environment. We also developed and actively maintain a comprehensive database that links life-history traits of the world’s 10,000 bird species with environmental and ecological data.